Getting Started With Biocontrol

Classical Biological Control of Weeds

Most invasive plants in North America are not native; they arrived with settlers, through commerce, or by accident from different parts of the world. These non-native plants are generally introduced without their natural enemies, the complex of organisms that feed on the plant in its native range. The lack of natural enemies is one reason non-native plant species become invasive pests when introduced in areas outside of their native range.

Biological control (also called “biocontrol”) of weeds is the deliberate use of living organisms to limit the abundance of a target weed. In this manual, biological control refers to “classical biological control,” which reunites host-specific natural enemies from the weed’s native range with the target weed in its introduced range. Natural enemies used in classical biological control of weeds include different organisms, such as insects, mites, nematodes, and pathogens. In North America, most weed biological control agents are plantfeeding insects, of which beetles, flies, and moths are among the most commonly used.

Biological control agents may attack a weed’s flowers, seeds, roots, foliage, and/or stems. Effective biological control agents seldom kill weeds outright, but work with other stressors such as moisture or nutrient shortages to reduce vigor and reproductive capability, or facilitate secondary infection from pathogens—all of which compromise the weed’s ability to compete with other plant species. Once established, root- and crown-feeding biocontrol agents are usually more effective on perennial plants that primarily spread by root buds. Flower- and seed-feeding biocontrol agents are typically more effective on annual or biennial plants that spread only by seed. Regardless of the plant part attacked by biocontrol agents, the aim is always to reduce populations and vigor of the target weed.

Although weed biological control is an effective and important weed management tool, it does not work in all cases and should not be expected to eradicate the target weed. Even in the most successful cases, biocontrol often requires multiple years before impacts become noticeable. When classical biological control alone does not result in an acceptable level of weed control, other weed control methods (e.g., physical, cultural, or chemical control) may be incorporated to achieve desired results. There are advantages and disadvantages to biological control of weeds as a management tool.

To be approved for release in North America, weed biocontrol agents must be host-specific, meaning they must develop only on the target weed. Rigorous testing is required to confirm that biocontrol agents are host specific and effective. Potential biocontrol agents often undergo five or more years of testing to ensure that rigid host specificity requirements are met, and results are vetted at a number of stages in the approval process.

The United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service - Plant Protection and Quarantine (USDA-APHIS-PPQ) is the federal regulatory agency responsible for providing testing guidelines and authorizing the importation of biocontrol agents into the USA. Though not currently found in Canada, if yellow starthistle were to become established in Canada, The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) serves the same regulatory role in Canada. Federal laws and regulations are in place to identify and avoid potential risks to native and economically valuable plants and animals that could result from exotic organisms introduced to manage weeds. The Technical Advisory Group (TAG) for Biological Control Agents of Weeds is an expert committee with representatives from USA federal regulatory, resource management, and environmental protection agencies, and regulatory counterparts from Canada and Mexico. TAG members review all petitions to import new biocontrol agents into the USA, and make recommendations to USDAAPHIS-PPQ regarding the safety and potential impact of prospective biocontrol agents. Weed biocontrol researchers work closely with USDA-APHIS-PPQ and TAG to accurately assess the environmental safety of potential weed biocontrol agents and programs. In addition, some states in the USA have their own approval process to permit field release of weed biocontrol agents. In Canada, the Biological Control Review Committee (BCRC) draws upon the expertise and perspectives of Canadian-based researchers (e.g., entomologists, botanists, ecologists, weed biological control scientists) from academic, government, and private sectors for scientific review of petitions submitted to the CFIA. The BCRC reviews submissions for compliance with the North American Plant Protection Organization’s (NAPPO) Regional Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (RSMP) No. 7. The BCRC also reviews submissions to APHIS. The BCRC conclusions factor into the final TAG recommendation to APHIS on whether to support the release of the proposed biocontrol agent in the USA. When release of a biocontrol agent is proposed for both the USA and Canada, APHIS and the CFIA attempt to coordinate decisions based on the assessed safety of each country’s plant resources.

Code of Best Practices

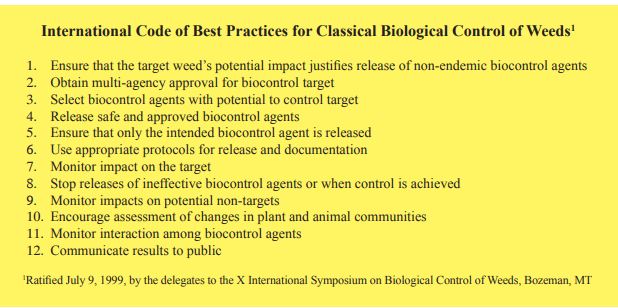

Biological control practitioners have adopted the International Code of Best Practices for Biological

Control of Weeds. The Code was developed in 1999 by delegates and participants in the Tenth International

Symposium for Biological Control of Weeds to both improve the efficacy of, and reduce potential negative

impacts from, weed biological control. In following the Code, practitioners reduce the potential for causing

environmental damage through the use of weed biological control by voluntarily restricting biocontrol

activities to those most likely to result in success and least likely to cause harm.

Is Biocontrol right for you?

When biological control is successful, biocontrol agents increase in abundance until they suppress (or contribute to the suppression of) the target weed. As local target weed populations are reduced, their biological control agent populations also decline due to starvation and/or dispersal to other target weed infestations. In many biocontrol systems, there are fluctuations over time with the target weed becoming more abundant, followed by increases of its biocontrol agent, until the target weed/biocontrol agent populations stabilize at a much lower abundance.

Biological control is not effective in every weed system or at every infestation. We recommend that you develop an integrated weed management program in which biological control is one of several control methods considered. Here are some questions you should ask before you begin a biological control program:

Is my management goal to eradicate the weed or reduce its abundance?

Biological control does not eradicate target weeds, so it is not a good fit with an eradication goal; however, depending on the target weed, which biological control agent is used, and land use, biological control can be effective at reducing the abundance and vigor of a target weed to an acceptable level.

How soon do I need results: this season, one to two seasons, or within five to ten years?

Biological control requires time and patience to work. Generally, it can take one to three years after release to confirm that biological control agents are established at a site, and even longer for biocontrol agents to cause significant impacts to the target weed. For some weed infestations, 5-30 years may be needed for biological control to reach its weed management potential.

What resources can I devote to my weed problem?

If you have only a small problem (less than 1 acre [0.4 ha] or much smaller), weed control methods such as hand pulling and/or herbicides, followed by regular monitoring for re-growth and retreatment when necessary, may be most effective. These intensive control methods may allow you to achieve rapid control and prevent the weed from spreading and infesting additional areas, especially when infestations occur in high-priority treatment areas such as travel corridors where the weed is more likely to readily disperse. If yellow starthistle is well established over a large area (>1 acre, 0.4 ha), and resources are limited, biological control may be the most economical weed control option.

Is the weed the problem, or a symptom of the problem?

Invasive plant infestations often occur where desirable plant communities have been or continue to be disturbed. Without restoration of a desirable, resilient plant community, and especially if disturbance continues, biological control is unlikely to solve your weed problems.

The ideal biological control program:

- Is based upon an understanding of the target weed, its habitat, land use and condition, and management objectives

- Is part of a broader integrated weed management program

- Has considered all weed control methods and determined that biological control is the best option based on available resources and weed management objectives

- Has realistic weed management goals and timetables

- Includes resources to ensure adequate monitoring of the target weed, the vegetation community, and populations of biological control agents

How to Implement a biocontrol program

When biological control is successful, biocontrol agents increase in abundance until they suppress (or contribute to the suppression of) the target weed. As local target weed populations are reduced, their biological control agent populations also decline due to starvation and/or dispersal to other target weed infestations. In many biocontrol systems, there are fluctuations over time with the target weed becoming more abundant, followed by increases of its biocontrol agent, until the target weed/biocontrol agent populations stabilize at a much lower abundance.

Select a site

Establish goals for your release site

You must consider your overall management goals for a given site when you evaluate its suitability for the release of biological control agents. Suitability factors will differ depending on whether the release is to be a:

- general release, where biological control agents are simply released for yellow starthistle management;

- field insectary (nursery) release, used primarily to mass produce biological control agents for redistribution to other sites; or

- research release, used to investigate biological control agent biology and/or the biocontrol agent’s impact on the target weed and non-target plant community. A site chosen to serve one of the roles listed above may also serve additional functions over time (e.g., biocontrol agents might eventually be collected for redistribution from a research or general release).

Determine Site Characteristics

Note Land Use and Disturbance Factors

Release sites should experience little to no regular disturbance. Abandoned fields/pastures, vacant lots, and natural areas are good choices for biological control agent releases. Sites where insecticides are used should not be utilized for biocontrol agent releases. Such sites include those near wetlands that are subject to mosquito abatement, rangelands that are subjected to grasshopper control, or infestations near agricultural fields or orchards where pesticide applications occur regularly. Roadside infestations along dirt or gravel roads with heavy traffic should also be avoided; extensive dust makes yellow starthistle plants less attractive to biocontrol agents. Do not use sites where significant land use changes will take place, such as road construction, cultivation, building construction, and mineral or petroleum extraction. If supply of biocontrol agents is limited, prioritize release sites that are not regularly mowed, burned, or treated with herbicides.

Survey for Presence of Biological Control Agents

Always examine your prospective release sites to determine if yellow starthistle biological control agents are already present. If a biocontrol agent you are planning to release is already established at a site, you may want to consider making the release at another site where the biocontrol agent is not yet present. If observed biocontrol agent populations are low at a site, you can release additional biocontrol agents at that site to augment the existing population.

Record Ownership and Access

If you release biological control agents on private land, it is a good idea to select sites on land likely to have long-standing, stable ownership and management. Stable ownership will help you establish long-term agreements with a landowner, permitting access to the sites to sample or harvest biological control agents and collect biocontrol agent and vegetation data for the duration of the project. This is particularly important if you are establishing a field insectary site, because five years or more of access may be required to complete biocontrol agent harvesting or data collection. General releases of biological control agents to control yellow starthistle populations require less-frequent and shortterm access; you may need to visit such a site only once or twice after initial release. When releasing biocontrol agents on private land, it may be a good idea to obtain the following:

- written permission from the landowner allowing use of the area as a release site

- written agreement with the landowner allowing access to the site for monitoring and collection for a period of at least six years (three years for establishment and buildup and three years for collection)

- permission to put a permanent marker at the site

- written agreement with the landowner that land management practices at the release site will not interfere with biological control agent activity

The above list can also be helpful for releases made on public land where the goal is to establish an insectary. In particular, an agreement should be reached that land management practices will not interfere with biological control agent activity (e.g., chemically spraying or physically destroying the weed infestation). It is often useful to visit the landowner or land manager at the release site annually to ensure they are reminded of the biological control endeavors and agreement. Always re-check with the landowner prior to inspecting release sites; in some cases the ownership may have changed.

You may wish to restrict access to release locations, especially research sites and insectaries, and allow only authorized project partners to visit the sites and collect biocontrol agents. The simplest approach is to select locations that are not visible to or accessible by the general public. To be practical, most if not all of your sites will be readily accessible, so in order to restrict access you should formalize arrangements with the landowner or manager. This will require you to post notrespassing signs, install locks on gates, etc. (Figure 4-4).

Another consideration is physical access to a release site. You will need to drive to or near the release locations, so determine if travel on access roads might be interrupted by periodic flooding or inclement weather. You might have to accommodate occasional road closures by private landowners and public land managers for other reasons, such as wildlife protection.

Select a weed

Coming Soon

Choosing the Appropriate Biological Control Agents for Release

You should consider several factors when considering which biological control agent to release at a site, including biocontrol agent efficacy, availability, and site preferences

Biocontrol Agent Efficacy

Efficacy refers to the ability of the biological control agent to directly or indirectly reduce the population of the target weed below acceptable damage thresholds or cause weed mortality resulting in control. It is preferable to release only the most effective biocontrol agents rather than releasing all biocontrol agents that might be available for a target weed. Consult with local weed biological control experts, neighboring land managers, and landowners to identify the biocontrol agent(s) that appear(s) more effective given local site characteristics and management scenarios.

Biocontrol Agent Availability

Federal and state departments or commercial biological control suppliers may be able to assist you in acquiring biocontrol agents not yet available but permitted for use in your area. In the United States, state departments of agriculture, county weed managers, extension educators, or federal and university weed biological control specialists should be able to recommend in-state collection sites where appropriate. Remember that in the United States, interstate transport of biological control agents requires a USDA-APHIS-PPQ 526 Permit. Get your permits early to avoid delays.

You do not need to take a lottery approach and release all approved biological control agents at a site in the hopes that one of them will work. Some biological control agents will not be available even if you want them, and some are already widespread and/or have been shown to have little or no effectiveness in certain Chapter 4: Elements of a Gorse and Scotch Broom Biological Control Program 81 areas. The best strategy is to release the best biocontrol agent. Ask the county, state, or federal biological control experts in your area for recommendations of biocontrol agents for your particular project.

If available, biological control agents from local sources are best. Using local sources increases the likelihood that biocontrol agents are adapted to the climate and site conditions present and are available at appropriate times for release at your target infestation. Using locally sourced biological control agents also reduces the possibility of accidentally introducing biocontrol agent pathogens or natural enemies to your area. Local sources may include neighboring properties or other locations in adjacent counties/districts.

Some USA states, counties, and universities have field collection days at productive insectary sites. On these days, land managers and landowners are invited to collect or receive locally collected biological control agents for quick release at other sites. These sessions are an easy and often inexpensive way for you to acquire biological control agents. They are good educational opportunities as well, because you may see first-hand any impacts the various biocontrol agents might be having on plant communities.

Typically, field days are conducted at several sites in a state and on several dates. Although designed for intrastate collection and redistribution, out-of-state participants may be welcome to participate (remember that USDA-APHISPPQ 526 Permits are required for interstate movement and release of biological control agents). Contact county weed supervisors, university weed or biological control specialists, or federal weed managers for information about field days in your region.

Release Site Characteristics

Need info here- General physical site and biological preferences for each biocontrol agent have been developed from anecdotal observations and experimental data. These are listed to help land managers ensure that biocontrol agents are released at sites with suitable conditions.

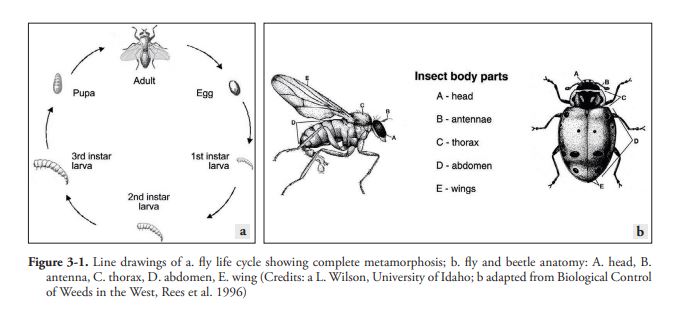

Insects

Insects are the largest and most diverse class of animals. Basic knowledge of insect anatomy and life cycles will help in understanding insects and recognizing them in the field. Most insects used in weed biocontrol have complete metamorphosis, which means they exhibit a life cycle with four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult (Figure 3-1a). All insects have an exoskeleton (a hard external skeleton) and a segmented body divided into three regions (head, thorax, and abdomen, Figure 3-1b). Adult insects have three pairs of segmented legs attached to the thorax, and a head with one pair each of compound eyes and antennae.

Because insects have an external skeleton, they must shed their skeleton in order to grow. This process of shedding the exoskeleton is called molting. Larval stages between molts are called “instars.” Larvae of insects with complete metamorphosis generally complete three to five instars before they molt into pupae. During the pupal stage, insects change from larvae to adults. Insects do not feed or molt during the pupal stage. Adult insects emerge from the pupal stage and do not grow or molt.

Beetles (Order Coleoptera)

Adult beetles are hard-bodied insects with tough exoskeletons. Adult beetles possess two pairs of wings. The two front wings, called elytra, are thickened and meet in a straight line down the abdomen, forming a hard, shell-like, protective covering (Figure 3-1b). The two hind wings are membranous and used for flight; these are larger and are folded under the elytra when not in use. Beetle larvae are grub- or worm-like with three small pairs of legs, allowing some to be quite mobile. Many are pale white with a brown or black head capsule, though some may be quite colorful and change markedly in appearance as they grow. All beetles have chewing mouth parts.

Flies (Order Diptera)

Many insects have the word “fly” in their name, though they may not be true flies. In the common names of true flies, “fly” is written as a separate word (e.g., house fly) to distinguish them from other orders of insects that use “fly” in their name (e.g., butterfly in the order Lepidoptera and mayfly in the order Ephemeroptera). Adult true flies are easily distinguished from other orders of insects by their single pair of membranous wings and typically soft bodies (Figure 3-1a,b). Larvae of most true flies, called maggots, are legless and worm-like.

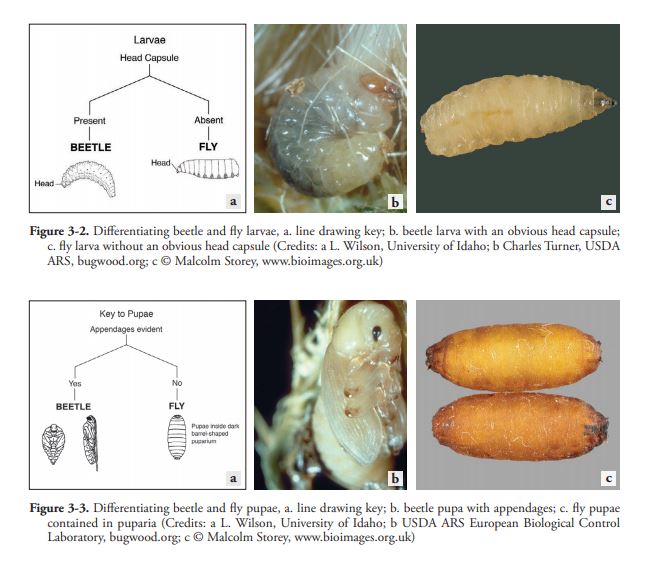

Differentiating Beetles and Flies

An important part of any successful biocontrol program is to be able to identify the biocontrol agents in the field. As adults, the insects are relatively easy to identify, with their variable size, form, color, and habits. The larvae are more challenging to identify than the adults, and yet are probably more important to recognize as this is the stage that 1) does the damage, 2) is monitored in the field, and 3) provides the best evidence that the insects are established in the field.

As illustrated in Figure 3-2a, the simplest method to determine if a larva found in yellow starthistle is a beetle or a fly is to look for a head capsule. Beetle larvae are as variable as adult beetles are, but all have an obvious head capsule (Figure 3-2b). Fly larvae have no obvious head capsule. Fly larvae are sometimes confused with other larvae because they appear to have a broad, dark head (Figure 3-2c); however, this is actually a dark, hardened anal plate that is used to anchor the larva to its host.

Figure 3-3a illustrates the differences between beetles and flies in the pupal stage. Beetle pupae have well-developed appendages that are obviously not fused to the body (Figure 3-3b). Fly pupae are

contained inside a puparium (Figure 3-3c).

Fungi

Fungi belong to their own kingdom (Fungi). The fungus described in this manual is a rust, which is in the phylum Basidiomycota. Rust fungi are obligate parasites; they require a living host to complete their life cycle. Rusts typically attack leaves and stems of the host plant. Rust infections usually appear as numerous rusty, orange, yellow, or even white colored spots (pustules) that rupture the leaf surface and release spores that resemble colored powder (typically yellow, orange, or brown). Most rust infections are local spots but some may spread internally through the plant. Rusts spread from plant to plant mostly by windblown spores, although insects, rain, and animals may aide in the transmission and infection process.

The life cycle of rust fungi can be very complicated. Rust fungi can produce up to five distinctive spore types which have different functions from infesting a new host plant, re-infecting the same host plant, producing pustules on infected plant leaves and stems, and overwintering.

Rust

Mite

Life cycles

Anatomy

Obtain Agents

Host specificity is a crucial point of consideration for a natural enemy to be released as a biological control agent. Host specificity is the extent to which a biological control agent can survive only on the target weed. Potential biological control agents often undergo more than five years of rigorous testing to ensure that host specificity requirements are met. These tests are necessary in order to ensure that the biological control agents are effective and that they will damage only the target weed.

You can obtain biological control agents by collecting or rearing them yourself, having someone collect them for you, or by purchasing them from a commercial supplier. This section provides information on collecting and purchasing biocontrol agents.

Factors to Conconsider When Looking for Sources of Biological Control Agents

You do not need to take a “lottery approach” and release all approved biological control agents at a site in the hopes that one of them will work. Some biological control agents will not be available even if you want them, and some are already widespread and/or have been shown to have little or no effectiveness in certain areas. The best strategy is to release the best biocontrol agent. Ask the county, state, or federal biological control experts in your area for recommendations of biocontrol agents for your particular project.

If available, biological control agents from local sources are best. Using local sources increases the likelihood that biocontrol agents are adapted to the climate and site conditions present and are available at appropriate times for release at your target infestation. Using locally sourced biological control agents also reduces the possibility of accidentally introducing biocontrol agent pathogens or natural enemies to your area. Local sources may include neighboring properties or locations in adjacent counties/districts. Remember that in the USA, interstate transport of biological control agents requires a USDA-APHIS-PPQ 526 Permit. Get your permits early to avoid delays.

Releasing Biological Control Agents

Establishing permanent location marker

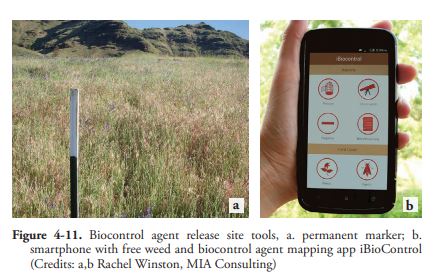

Place a steel fence post or plastic/fiberglass pole as a marker at the release point (Figure 4-11a). Avoid wooden posts; they are vulnerable to weather and decay. Markers should be colorful and conspicuous. White, bright orange, pink, and red are preferred over yellow and green, which may blend into surrounding vegetation. In addition, white posts will not fade over time. Where conspicuous posts may encourage vandalism, mark your release sites with short, colorful plastic tent/surveyor’s stakes or steel plates that can be tagged with release information and located later with a metal detector and GPS. Depending on the land ownership or management status at the release site, it may be necessary to attach a sign to the post or pole indicating a biological control release has occurred there and that the site should not be sprayed with chemicals or be mechanically disturbed (see Figure 4-4 on page 52). Where a sign is appropriate, the landowner/land manager and the local weed management authority (county, state, federal, and/or provincial) should be notified and given a map of the release location.

Record geographical coordinates at release point using GPS

Map coordinates of the site marker should be determined using a global positioning system device (GPS) or a GPS-capable tablet/smartphone. There are numerous free apps available for recording GPS coordinates on a tablet/smartphone (Figure 4-11b). Coordinates should complement but not replace a physical marker. Accurate coordinates will help re-locate release points if markers are damaged or removed. Along with the coordinates, be sure to record what coordinate system and datum you are using, e.g., latitude/longitude in WGS 84 or UTM in NAD83.

Prepare Map

The map should be detailedand describe access to the release site, including roads, trails, and unique landmarks/terrain features that are not likely to change through time (e.g., large rocks or rocky outcrops, creeks, valleys, etc.). Avoid using ephemeral landmarks such as “red bush”, “grazing cows”, etc. and descriptors which may not be obvious to everyone, such as “the Miller place”, or “where the old barn used to be”, etc.. Use your vehicle’s trip odometer to measure and record mileage between specified locations on your map, e.g., when you turn on to a new road, at cattle guards along the route, and where you park. The map should complement but not replace a physical marker and GPS coordinates. Maps are especially useful for long-term biological control programs in which more than one person will be involved or participants are likely to change. Maps are often necessary to locate release sites in remote locations or places physically difficult or confusing to access.

Complete relevant paperwork at site

Your local land management agency/authority may have standard biocontrol agent release forms for you to complete. Typically, the information you provide includes a description of the site’s physical location, including GPS-derived latitude, longitude, and elevation; a summary of its biological and physical characteristics and land use; the name(s) of the target weed and biocontrol agent(s) released; the number and life cycle stage of the agent(s) released; date and time of the release; weather conditions during the release; and the name(s) of the person(s) who released the biocontrol agents . The best time to record this information is while you are at the field site. Consider using a smartphone and reporting app such as iBioControl. This free application uses EDDMapS to help county, state, and federal agencies track releases and occurrences of biological control agents of noxious weeds. Once back in the office, submit the information to your local weed control office, land management agency, or other relevant authority/database. Always keep a copy for your own records.

Set up a photo point

A photo point is used to visually document changes in yellow starthistle infestations and other components of the plant community over time following the release of biocontrol agents. Use a permanent feature in the background as a reference point (e.g., a mountain, large rocks, trees, or a permanent structure) and make sure each photo includes your release point marker. Pre- and postrelease photographs should be taken from roughly the same place and at the same time of year. Label all photos with the year and location; many smartphone and tablet apps such as GrassSnap or Theodolite do this automatically or with minimal input

Monitoring the site

The Need for Documentation

The purpose of monitoring is to evaluate the success of your gorse and broom biological control program and to determine if you are meeting your weed management goals. Documenting outcomes (both successes and failures) of biocontrol release programs will help generate a more complete picture of biocontrol impacts, guide future management strategies, and serve education and public relations functions. Monitoring can provide critical information for other land managers by helping them predict where and when biological control might be successful, helping them avoid releasing ineffective biocontrol agents or the same biocontrol agent in an area where they were previously released, and/or helping them avoid land management activities that would harm local biocontrol agent populations or worsen the gorse and broom problem.

Monitoring activities utilize standardized procedures over time to assess changes in populations of the biocontrol agents, gorse and broom, other plants in the community, and other components of the community. Monitoring can help determine:

Monitoring methods can be simple or complex. A single year of monitoring may demonstrate whether the biocontrol agents established, while multiple years of monitoring may allow you to identify trends in the population of the biocontrol agents, changes in the target weed population and plant community, and changes in other factors such as climate or soil.

Information Databases

Many federal and state/provincial departments have electronic databases for archiving information about weed biological control releases. We have included a standardized biological control agent release form (insert link here)that, when completed, should provide sufficient information for inclusion in any number of databases.

Biological Control of Weeds: A World Catalogue of Agents and their Target Weeds (database)

The USDA Forest Service (in conjunction with the University of Georgia, MIA Consulting, University of Idaho, CAB International, and the Queensland Government) also maintains a worldwide database for the Biological Control of Weeds: A World Catalogue of Agents and their Target Weeds. The database includes entries for all weed biocontrol agents released to date, including the year of first release within each country, the biocontrol agents’ current overall abundance and impact in each country, and more.

Integrated Management Program

The invasion curve (Figure 5-1) shows that eradication of an invasive species becomes less likely and control costs increase as an invasive species spreads over time. Prevention is the most cost-effective solution, followed by eradication. If a species is not detected and removed early, intense and long-term control efforts will be unavoidable. Identifying where your species is on the invasion curve in a particular area is the first step to taking management action. Inventorying and mapping current populations coupled with research efforts to predict where it is most likely to move enables land managers to concentrate resources in areas which are likely to be invaded, and then to treat individual plants and small populations before it is too late to remove them.

A wide variety of successful weed control methods have been developed and may be useful for helping meet management goals. The most successful long-term management efforts have a number of common features, including:

- Education and Outreach

- Inventory and Monitoring

- Prevention

- Weed Control Activities: A variety of control activities which are selected based

on characteristics of the target infestation and planned in advance to use the most appropriate method or combination of methods at each site, including:

- Biological control

- Physical treatment

- Cultural practices

- Chemical treatment

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) incorporates all efforts noted above, and addresses several aspects of land management, not just how to get rid of weed populations. Land managers or landowners engaged in IPM take the time to educate themselves and others about the threat invasive species pose to the land and how management may facilitate invasion. IPM requires land managers to regularly inventory and map the land they manage, identifying areas where the vegetation is not meeting their management objectives and identifying reasons why. When a weed infestation is found, IPM dictates that land managers map it and make plans to address it utilizing control methods most appropriate for their particular infestation and land use. After initiating control activities, IPM encourages land managers to monitor the site to determine if the control activity was successful in subsequent years. If re-treatment or additional treatments are necessary, these are applied in a timely manner with appropriate post-treatment monitoring to ensure that management objectives are being met.

Integrated Pest Management programs undertaken on a landscape level over many years can, at times, prove logistically difficult, expensive, and time-consuming. The concept of Cooperative Weed Management Areas (CWMA) was created in the western USA in order to erase jurisdictional boundaries as an impediment to weed control and make a landscape IPM approach to weed management more feasible and successful. CWMAs consist of federal, state and local land managers, as well as concerned private landowners, within a designated zone who combine and coordinate efforts against exotic plants, pooling and stretching limited resources and labor for managing invasive species and protecting/restoring habitat. Cooperation between neighboring CWMAs helps transfer knowledge and experience between heavily treated regions and places not yet as impacted. Sharing successes and failures in management saves time and funding and reduces the incidence of both failure and negative impacts from management efforts, such as destruction of wildlife habitat and damage to non-target species. Numerous CWMAs exist throughout the western states of the USA and are excellent sources of information, experience, and resources for treating infestations using an IPM approach.