In North America, the majority of plants we consider to be really invasive are not native here; many arrived by accident as contaminants in crop seed, some were intentionally planted by European settlers for their medicinal value, and others were introduced as garden plants before they escaped and spread. These non-native plants are generally introduced without their natural enemies—the insects, mites, pathogens and etc. that help keep their populations in check in their native ranges. A lack of natural enemies is thought to be one of the main reasons why some plant species become so invasive when introduced to areas outside of their native range. This theory is known as the enemy release hypothesis.

Classical weed biological control (referred to simply as biocontrol throughout this website) is the intentional importation and use of a weed’s natural enemies to reduce its vigor and reproductive potential. Weed biocontrol is regulated, and only biocontrol agents that have been tested and are host-specific to the target weed will be permitted for use in North America. Biocontrol agents may attack a weed’s flowers, seeds, roots, foliage, and/or stems, reducing the competitive advantage of many weed species and giving the competitive edge back to native or more desirable plants.

There are other kinds of biocontrol; for example, augmentative biocontrol is often used to help control pest insect and mites in an agricultural setting. There are also many misconceptions about classical biological control. For example, when landowners in the Caribbean intentionally introduced the Javan mongoose to control black rats, or when the cane toad was introduced to Australia to control a sugar cane pest, these disastrous actions had nothing to do with the discipline of classical biological control. True classical weed biocontrol utilizes rigorous testing to identify natural enemies specific to (that attack only) the target weed in the native range for release into the introduced range.

Biocontrol is just one of many weed control options available. Other options include chemical control with pesticides, physical control with tilling, mowing or digging, and cultural control with land management practices. The best weed control method will depend on your infestation, your management goals, and your available resources.

Determining whether or not biocontrol is an appropriate choice for your situation will depend on a number of factors, including the location and traits of the target infestation, the weed being targeted, the biocontrol agents available, your management goals, and what resources you have to devote to your weed management program. Below are questions you should ask before you begin a biocontrol program:

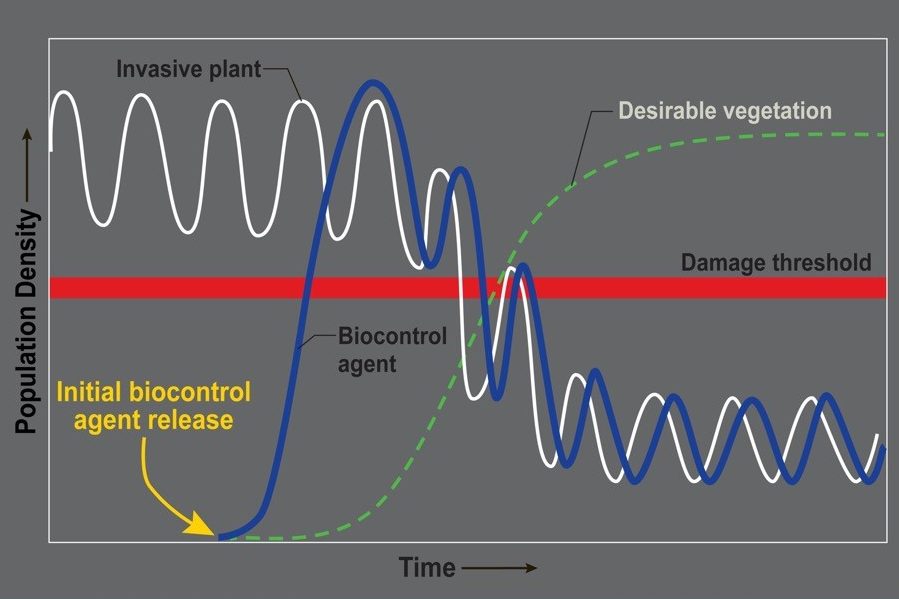

The invasion curve diagram demonstrates the stages of invasion typical for many invasive species. When a weed newly establishes, populations often remain small for the first year or so, and then either gradually or sometimes rapidly colonize the region. Weed infestations have the greatest probability for successful control if they are managed in the early stages of invasion when populations are small and eradication is possible. Because biocontrol takes time and does not eradicate weeds, it is not the appropriate choice during the early stages of the plant invasion. Control options that can achieve immediate eradication of a very small population would be a better choice, e.g., hand-pulling or spot-spraying with herbicides followed by regular monitoring and re-treatment as necessary to ensure the population is eradicated. These intensive control methods may allow you to achieve rapid control and prevent the weed from spreading and infesting additional areas, especially when infestations occur in high-priority treatment areas such as travel corridors where the weed is more likely to readily disperse. Biocontrol is best suited to the containment and asset-based protection stages of the invasion curve. These include infestations that are established over a large area with one or many populations that are a minimum of ¼ acre (0.1 ha) in size. Biocontrol is also well suited to infestations where access and/or funding are limited, or in sensitive areas where other control methods are not suitable such as in riparian areas or where protected species also occur.

Biocontrol does not eradicate a target weed. For new and very small populations of weeds, other forms of treatment (such as hand-pulling or spot-spraying) are more appropriate in order to achieve immediate eradication. Biocontrol is best suited to large infestations, where access is limited, in sensitive areas, or where funding is limited.

Because of the extensive and expensive requirements for developing and officially approving biocontrol agents, many weeds do not have biocontrol agents available. Even when agents have been approved for your target weed, not all of them may be suitable for your climate, location, or situation, and the approval of some established biocontrol agents has since been revoked. Contact your nearest biocontrol specialist or search the Weed Biocontrol Agent or Library sections of this website to learn if there are approved biocontrol agents available for your target weed and to determine if they would be well suited to your location.

Biocontrol requires time and patience to work. Generally, it can take one to three years after release to confirm that biocontrol agents are established at a site, and even longer for biocontrol agents to cause significant impacts to the target weed. For some weed infestations, 5–30 years may be needed for biocontrol to reach its weed management potential.

Weed infestations often occur where desirable plant communities have been or continue to be disturbed. Without restoration of a desirable, resilient plant community, and especially if disturbance continues, biocontrol is unlikely to solve your weed problems.

The ideal biocontrol program:

When biocontrol is determined to be suitable for treating your weed infestations, there are some important points to consider, including selecting appropriate release sites, choosing the best biocontrol agents for your area, obtaining and releasing biocontrol agents, and monitoring the success of the biocontrol program. Familiarity with all aspects of a biocontrol program before starting one will greatly help with its implementation and increase your chances of success. Each of these items is discussed in the next section of the website.

The effectiveness of weed biocontrol depends on the land manager’s definition of success, and this varies from place to place, depending on the goals and objectives of the weed control project.

Some biocontrol agent introductions have resulted in spectacular reductions of their target weeds. For example, in the 1990s, Dalmatian toadflax was smothering large tracts of land in western North America and was spreading rapidly. Releases of the beetle Mecinus janthiniformis began controlling the majority of Dalmatian toadflax infestations within two decades, as seen in the images below. This scale of destruction is uncommon for biocontrol, however. In some instances, biocontrol agents have had little to no impact on their target weeds, for a variety of reasons. Most biocontrol programs are considered successful when the target weeds are still present but reduced to the point where the damage they cause is below an acceptable economic or ecological threshold.

Dalmatian toadflax infestation before and after the release of Mecinus janthiniformis.

Target weed infestations regularly fluctuate, but their levels are originally above the damage threshold where they cause economic and ecological harm. This is illustrated in the graph below. When biocontrol is successful, biocontrol agents increase in abundance until they help suppress the target weed to levels below the damage threshold. As local target weed populations are reduced, their biocontrol agent populations also decline, due to starvation or the agents dispersing to other target weed infestations. In many biocontrol systems, there are fluctuations over time with the target weed becoming more abundant, followed by increases of its biocontrol agent, until the target weed and biocontrol agent populations stabilize at a much lower abundance. Generally, it can take one to three years after release to confirm that biocontrol agents are established at a site, and even longer to cause significant impacts to populations of the target weed. For some weed infestations, 5–30 years may be needed for biocontrol to reach its weed management potential.

In the example above, Dalmatian toadflax was the dominant plant species at this site in North America in the 1990s when it was above the damage threshold due to its crowding out of native and more desirable species. Releases of Mecinus janthiniformis were made in 2009. As the graphs below illustrate, by 2014, M. janthiniformis populations had increased sufficiently to reduce Dalmatian toadflax levels to below the damage threshold. The reuniting of M. janthiniformis and its host Dalmatian toadflax has brought the Dalmatian toadflax infestation at this site to levels closer to those observed in the native range in Europe. Although Dalmatian toadflax is still present at this site in North America, it is no longer a significant economic or ecological concern.

These graphs illustrate the changes and fluctuations in Mecinus janthiniformis populations and the height, number of stems, and cover of Dalmatian toadflax at one site in Idaho since the agent was released in 2009.

It is important to bear in mind that in the weed’s native range, the weed is a fixed component of the plant community. Because the goal of weed biocontrol is to restore the balance between a weed and its natural enemies, eradication should never be the goal for this form of weed control.

Dalmatian toadflax growing in its native range in Europe.

Although weed biocontrol is an effective and important weed management tool, it does not work in all cases and should not be expected to eradicate the target weed. Even in the most successful cases, biocontrol often requires multiple years before impacts become noticeable. When classical biocontrol alone does not result in an acceptable level of weed control, biocontrol should be part of an Integrated Pest Management program incorporating other weed control methods (e.g., physical, cultural, or chemical control) to achieve desired results. There are advantages and disadvantages to biocontrol of weeds as a management tool:

Classical weed biocontrol programs begin with exploration for specialized natural enemies affecting weeds in their area of origin. This process includes physically surveying weeds for their natural enemies in their native range, as well as reviewing relevant published literature. Potential biocontrol agents identified during foreign exploration are then subjected to testing to show they attack only the target weed and that they are potentially effective. The results of this testing are reviewed at several stages during the agent approval process, which are described in greater detail in the “Safety” section below. After a biocontrol agent is approved for introduction into North America, it is released in the field. In ideal situations, biocontrol agent release sites are monitored before, during, and for several years after releases to gather data demonstrating the impacts of the release.

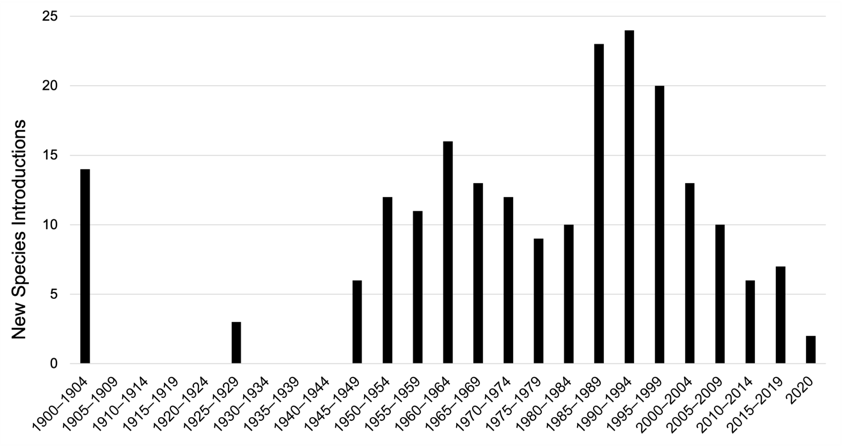

The first intentional use of classical weed biocontrol dates back to the mid-1800s when scale insects were intentionally released and redistributed around India and surrounding countries for the control of invasive cactus species. Since then, over 500 biocontrol agents have been released on over 210 weeds in more than 95 countries worldwide. In the United States, the first biocontrol agent release was made in 1902. By the year 2020, over 200 biocontrol agents had been introduced against 79 weed species.

Beginning in the 1940s, introductions of weed biocontrol agents in the continental United States were regulated under the Plant Quarantine Act of 1912 which required the testing of potential agents against locally important crops to ensure their safety. In 1973, the Endangered Species Act was passed in the United States, with the goal of protecting rare or threatened native species. In this same time period, the goal of ensuring that introduced plant biocontrol agents would not damage economic plants was expanded to protect native plants. While rare plants received special attention in testing, the goal was to protect all native plants from any significant population-level damage. This caused the testing protocol applied to candidate agents to shift from being just an exclusionary exercise (providing evidence of lack of attack on a small list of particular crops) to estimating the boundaries of the agent’s host range so as to be predictive of risk for untested species. This was achieved by testing plants at various taxonomic distances from the target weed, using the centrifugal method of Wapshere (1974). Improvements in the science of host range estimation have continued, with increased focus on the role of host preference among accepted plants and the role of olfactory and visual cues causing foraging adults to seek out specific plant species for oviposition, development, and feeding.

True classical weed biocontrol requires rigorous testing to prove that biocontrol agents are host-specific, meaning they develop only on the target weed.

In North America, the host specificity process of weed biocontrol has improved greatly over the past 200 years. Some of the earliest organisms to be released were not thoroughly vetted before their release and were later found feeding on more than just their target weed. Since then, very strict regulations and testing standards have been established.

The United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service – Plant Protection and Quarantine (USDA APHIS PPQ) is the federal regulatory agency responsible for providing testing guidelines and authorizing the importation of biocontrol agents into the USA. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) serves the same regulatory role in Canada. Federal laws and regulations are in place to identify and avoid potential risks to native and economically valuable plants and animals that could result from exotic organisms introduced to manage weeds. The Technical Advisory Group (TAG) for Biological Control Agents of Weeds is an expert committee with representatives from USA federal regulatory, resource management, and environmental protection agencies, and regulatory counterparts from Canada and Mexico. TAG members review all petitions to import new biocontrol agents into the USA and make recommendations to USDA APHIS PPQ regarding the safety and potential impact of prospective biocontrol agents. Weed biocontrol researchers work closely with USDA APHIS PPQ and TAG to accurately assess the environmental safety of potential weed biocontrol agents and programs. In addition, some states in the USA have their own approval process to permit field release of weed biocontrol agents. In Canada, the Biological Control Review Committee (BCRC) draws upon the expertise and perspectives of Canadian-based researchers (e.g., entomologists, botanists, ecologists, weed biocontrol scientists) from academic, government, and private sectors for scientific review of petitions submitted to the CFIA. The BCRC reviews submissions for compliance with the North American Plant Protection Organization’s (NAPPO) Regional Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (RSMP) No. 7. The BCRC also reviews submissions to APHIS. The BCRC conclusions factor into the final TAG recommendation to APHIS on whether to support the release of the proposed biocontrol agent in the USA. When release of a biocontrol agent is proposed for both the USA and Canada, APHIS and the CFIA attempt to coordinate decisions based on the assessed safety of each country’s plant resources.

There are many misconceptions about weed biocontrol. For example, when landowners in the Caribbean intentionally introduced the Javan mongoose to control black rats, or when the cane toad was introduced to Australia to control a sugar cane pest, these disastrous actions had nothing to do with the discipline of classical weed biocontrol.

Biocontrol practitioners have adopted the International Code of Best Practices for Biological Control of Weeds. The Code was developed in 1999 by delegates and participants in the Tenth International Symposium for Biological Control of Weeds to both improve the efficacy of, and reduce potential negative impacts from, weed biocontrol. In following the Code, practitioners reduce the potential for causing environmental damage through the use of weed biocontrol by voluntarily restricting biocontrol activities to those most likely to result in success and least likely to cause harm.

International Code of Best Practices for Classical Biological Control of Weeds1

1Ratified July 9, 1999, by the delegates to the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, Bozeman, MT

See the FAQ section for additional discussions pertaining to the safety of classical weed biocontrol.