When biocontrol is determined to be suitable for treating your weed infestations, there are some important points to consider, including selecting appropriate release sites, choosing the best biocontrol agents for your area, obtaining and releasing biocontrol agents, and monitoring the success of the biocontrol program. Familiarity with all aspects of a biocontrol program before starting one will greatly help with its implementation and increase your chances of success. Each of these items is discussed in detail throughout this section.

Several factors must be considered when determining if infestations are appropriate for releasing biocontrol agents. These include the physical characteristics of the release site, the current land use at the site, whether or not biocontrol agents are already present, current and future ownership, and access to the site.

No weed infestation is too large for biocontrol releases; however, it might not be large enough. Really small, isolated patches of your target weed will probably not be adequate for biocontrol agent populations to build up and persist and are often better treated with other weed control methods, such as physical control or herbicides. An area with at least ¼ acre (0.1 ha) of your target weed is typically the minimum size to ensure a successful biocontrol agent release site, but larger infestations are more desirable, especially if you or the land manager hope to someday use the release site as a field insectary. This is a nursery site where the biocontrol agent has become so abundant that you can collect it for release elsewhere. However, smaller infestations may be acceptable release sites in some cases, such as critical habitat zones where disturbance from physical or chemical control could be detrimental or sites where herbicides are prohibited. Regardless of the infestation size, biocontrol agents disperse more easily in contiguous weed infestations, rather than infestations with only a few scattered plants and distant patches.

Because weeds grow in a variety of habitats, potential release sites are likely to vary in their suitability for biocontrol. Furthermore, different biocontrol agents have varying habitat requirements, so the suitability of a site is difficult to predict in advance. Consequently, making multiple releases into separate sites will provide more opportunities for at least one population to establish in each region. More releases will also increase the likelihood that there is at least one very robust population that can serve as a nursery site to supply future releases.

Tansy ragwort infestations appropriate for biocontrol and too small for biocontrol release.

Biocontrol release sites should experience little (or even better no) regular disturbance to allow biocontrol agent populations to build. Abandoned fields, vacant lots, and natural areas are good choices for releases. Sites where insecticides are used should not receive releases. Such sites include those near wetlands that are subject to mosquito abatement, rangelands that are subjected to grasshopper control, or infestations near agricultural fields or orchards where pesticide applications occur regularly. Roadside infestations along dirt or gravel roads with heavy traffic should also sometimes be avoided because extensive dust makes plants less palatable to biocontrol agents. Do not use sites where significant land use changes will take place, such as road construction, cultivation, building construction, and mineral or petroleum extraction. If supply of biocontrol agents is limited, prioritize release sites that are not regularly mowed, burned, or treated with herbicides.

Dyer’s woad infestations appropriate for biocontrol and inappropriate for biocontrol. The second site is inappropriate because it is in an active construction zone.

Always examine your prospective release sites to determine if biocontrol agents are already present. This can be confirmed by finding the biocontrol agent in any of its life stages or by identifying its characteristic damage. If a biocontrol agent you are planning to release is already established at a site, you may want to consider making the release at another site where it’s not yet present. If a biocontrol agent is observed but populations are low, you can still release additional biocontrol agents at that site to augment the existing population.

Searching a Dalmatian toadflax site and finding Mecinus janthiniformis already present.

It is a good idea to select sites on land likely to have long-standing, stable ownership and management. This will help you establish long-term agreements with a landowner that will permit access to the sites to sample or harvest biocontrol agents, collect monitoring data for the duration of the project, and ensure that land management practices won’t interfere with biocontrol agent activity (e.g., chemically spraying or physically destroying the weed infestation). Always re-check with the landowner prior to inspecting release sites; in some cases, the ownership may have changed. If your biocontrol program goals involve evaluating the program’s effectiveness, establish permanent monitoring sites before you release any biocontrol agents. Refer to the “Monitoring” section, below, for details on ways to do so. The monitoring sites will require regular inspections, so consider the site’s ease of accessibility, terrain, and slope. Finally, you may wish to restrict access to release locations, especially research sites and insectaries, and allow only authorized project partners to visit the sites and collect biocontrol agents. This will require you to post no-trespassing signs, install locks on gates, etc.

Ensure release sites are physically accessible and that you have an agreement with the landowner. Travis McMahon, MIA Consulting.

Sometimes, multiple biocontrol agents are available for one target weed. You should consider several factors when deciding which ones to release at a site, including their effectiveness, availability, and site preferences.

The most effective biocontrol agents are able to directly or indirectly reduce the abundance of the target weed population to acceptable levels. It’s better to release only the most effective biocontrol agents rather than releasing all agents that might be available for a target weed. This is because some biocontrol agents are only effective in some habitats or climates and some agents may compete or interfere with one another.

For example, the Microlarinus puncturevine weevils are severely limited by cold winter temperatures. While these weevils have dramatically reduced puncturevine populations at some warm, low-elevation sites in southern California, Alabama, and Hawaii, winter temperatures in the Pacific Northwest are generally too cold to sustain weevil populations large enough to provide adequate control of puncturevine. In a different example, there are several knapweed biocontrol agents established and available in North America. Many of these are seed feeders or gallers and have been shown to compete or interfere with each other, sometimes reducing overall effectiveness when combined.

Consult with your local weed biocontrol experts, neighboring land managers, or the Library on this website to identify the biocontrol agents that appear most effective given your local site characteristics and management scenarios.

Several approved biocontrol agents are currently established in continental North America, though their availability varies greatly between species and sites. Contact your nearest biocontrol specialist to learn if there are approved biocontrol agents available for your target weed and to determine if they would be well suited to your location.

Some unintentionally introduced species are also established on several weeds in North America. Most of these are not approved for redistribution in the USA. Because many of these resemble approved species, they could be accidentally collected and redistributed along with the approved species. Refer to the resources listed in the Weed Biocontrol Agent section of this website or check with your local weed biocontrol experts and extension educators to learn about unapproved species you may encounter when working with biocontrol agents on your target weed.

Chaetorellia australis is approved for redistribution on yellow starthistle in the USA while the accidentally introduced Chaetorellia succinea is widely established but not approved for redistribution.

Once you’ve narrowed down the best choice of biocontrol agents for your target weed, you can obtain individuals in a variety of ways, including having someone collect them for you, collecting or rearing them yourself, or purchasing them from a commercial supplier. Regardless of how you obtain them, biocontrol agents from local sources are best. Using local sources increases the likelihood that biocontrol agents are adapted to the climate and site conditions at your site and are available at appropriate times for release at your target infestation. Using locally sourced biocontrol agents also reduces the possibility of accidentally introducing biocontrol agent pathogens or natural enemies to your area. Local sources may include neighboring properties or other locations in adjacent counties/districts. In the USA, transporting many biocontrol agents across state lines requires a special permit. In most states, a weed manager will have both biocontrol agents and valid permits so check with your local weed biocontrol specialist first.

Before you obtain biocontrol agents, familiarize yourself with the proper way to care for your biocontrol agents and ensure you have the necessary supplies on hand. Biocontrol agents should be maintained in containers intended to protect them and to keep them from escaping en route to the release site. Containers should be rigid to resist crushing and ventilated to provide adequate air flow and prevent condensation. Unwaxed paperboard cartons are ideal for most species. Alternatively, you can use light-colored, lined containers (such as ice cream cartons) or plastic containers, as long as they’re ventilated. Cut or poke holes in the container or its lid, and cover the holes with a fine mesh screen. Do not use glass or metal release containers; they are breakable and make it difficult to regulate temperature, airflow, and humidity.

For insects, fill containers with crumpled tissue paper to provide a substrate for insects to rest on and hide in, and to help regulate humidity. Include several fresh sprigs of the target weed foliage. Sprigs should be free of roots, seeds, flowers, dirt, spiders, and other insects. Do not place sprigs in water-filled containers; they may crush the biocontrol agents or drown them upon leaking. Seal the container lids either with masking tape or rubber bands. Be sure to label each container with (at least) the name and number of biocontrol agent(s), the collection date and site, and the name of the person(s) who did the collecting. When infested stems or foliage are used for redistribution, the plant material should be stored in sealable but breathable bags made of paper or gauze. Plastic bags may cause moist plant material to rot or drown the biocontrol agents. Infested plant material should be kept cool at all times to avoid deterioration during hot summer months.

If you sort and package your agents indoors, keep them in a refrigerator (no lower than 40°F or 4°C) until you transport or ship them (which should occur as soon as possible but no longer than 48 hours). For biocontrol species that hibernate within target weed material over winter (e.g., some beetle species), infested plant material can be kept in cold storage overwinter and then transferred the following spring. Plant material must be retained under consistently cold, moist conditions (ideally 40–46°F, 4–8°C) at ~60% humidity) to keep biocontrol agents alive and discourage them from leaving the stems until host plants begin growing on release sites the following spring. For additional information on storing and transporting biocontrol agents, refer to this supplementary fact sheet, or watch these storage and transportation videos.

Containers should be rigid but ventilated and be filled with crumpled tissue paper to regulate humidity and to provide a substrate for insects to rest on and hide in.

The best time of year for obtaining biocontrol agents depends on the biocontrol agent species and the stage of development for your target weed species growing at your release site. This type of information can be found in many useful extension publications, such as the Field Guides for Biological Control of Weeds in the Northwest and Eastern North America. These and other useful publications can all be found in the Library on this website. You can also contact your local or state weed biocontrol authority for timing suggestions specific to your area.

Some US states, counties, and universities organize “field days” at a productive insectary. On these days, land managers and landowners are invited to collect or receive locally collected biocontrol agents for quick release at other sites. These sessions are good educational opportunities for learning how to implement a biocontrol program on your target weed, and you may see first-hand any impacts the various biocontrol agents might be having on plant communities. Contact your county weed manager, extension educator, or university weed or biocontrol specialist for information about field days in your region.

There are several methods for field collecting weed biocontrol agents. The best method depends on the species being collected, the abundance of the biocontrol agent at the collection site, the target weed, and the conditions at the collection site. Some of the most common methods include sweep netting with or without aspirating, hand-picking/tapping, vacuuming, light traps, and transferring infested plant material. These are described in greater detail in this supplementary fact sheet and in the video. For information on storing and transporting biocontrol agents you collect yourself, refer to this supplementary fact sheet, or watch these storage and transportation videos.

Weed or biocontrol specialists will typically be able to recommend one or more suppliers. Make sure that a prospective supplier is reputable, can provide healthy individuals of the species you want (parasite- and pathogen-free), and can deliver them to your area at a time appropriate for field release (you will want to know where and when the biocontrol agents were collected). Avoid purchasing biocontrol agents from a supplier who collects biocontrol agents from an environment significantly different from your planned release location because the agents are more likely to have difficulty establishing. If the seller is from another state, confirm in advance that the seller has a permit in place for the species you are acquiring as well as the region in which the release will occur. ONLY purchase or release approved biocontrol organisms. Contact your local biocontrol specialist before purchasing biocontrol agents.

The preferred collection method for delicate insects such as moths or flies is to rear the adults out indoors. This method is also useful for biocontrol agents plagued by parasitoids or microorganisms/diseases so you ensure you don’t spread those to new sites. Target weed material infested with larvae or pupae of your desired biocontrol agent can be collected in the fall or winter and stored either in a fridge set at 40–46°F (4–8°C) or even in an unheated place such as a garage or shed if you live in a cold climate. Two to three weeks prior to their normal emergence time, bring them to room temperature in fine mesh rearing cages or breathable, clear containers. Any parasitoids that emerge should be separated and destroyed; many of these look like tiny wasps. Emerging biocontrol agents can be transferred to new target weed patches during the appropriate plant stage. Timing information specific to your target biocontrol agent can be found in various extension publications which are available in the Library on this website. For information on storing and transporting biocontrol agents you rear yourself, refer to this supplementary fact sheet, or watch these storage and transportation videos. Care should be taken to ensure that all emerging and transferred species are indeed the desired biocontrol agent. Remember, there are many look-alike species not approved for redistribution.

Rearing cages are used to collect biocontrol agents emerging from weed tissue or galls. Any emerging parasitoids that emerge should be destroyed. Tthe braconid wasp Microplitis rufiventris is a parasitoid of the Egyptian cottonworm, Spodoptera littoralis.

Before releasing biocontrol agents, it is necessary to first prepare the release site by establishing a permanent location marker. The site should then be photographed, and information pertaining to the site and upcoming release should be collected, both of which can be completed with the iBiocontrol app.

Place a steel fence post or plastic/fiberglass pole as a marker at the release point to make the point easier to find in future visits. Avoid wooden posts; they are vulnerable to weather and decay. Markers should be colorful and conspicuous. White, bright orange, pink, and red are often preferred over yellow and green, which may blend into surrounding vegetation. If you’re in a place where conspicuous posts might encourage vandalism, mark your release sites with short, colorful plastic tent/surveyor’s stakes or steel plates that can be tagged with release information and located later with a metal detector and GPS. Depending on the land ownership or management status at the release site, it may be necessary to attach a sign to the post or pole indicating a biocontrol release has occurred there and that the site should not be sprayed with chemicals or be mechanically disturbed.

Colorful posts should be used to mark release sites. Where conspicuous markers may encourage vandalism, a smaller stake with a steel plate/tag can be used instead and located later with a metal detector. At some sites, it may be helpful to post a sign indicating a release has occurred and that the site should not be disturbed.

After establishing a permanent marker, it is necessary to gather information about the site that will help you revisit the location in future years and better analyze the results of the release at that site. This information can be gathered most quickly and easily using the iBiocontrol app. Download the app for your preferred device. This free application uses EDDMapS, a web-based mapping system increasingly being used to help county, state, and federal agencies track releases and occurrences of biocontrol agents as well as invasive species in North America.

Upon opening the iBiocontrol app, give the site a unique name1 that will help you differentiate it from other release sites in the vicinity. Enter the weed being targeted2, as well as the biocontrol agent being released3, the number being released4, and the developmental stage of the agent5. Tap the camera6 to add a photo; you will be prompted to take a new photo with your device or select an image already saved to your device.

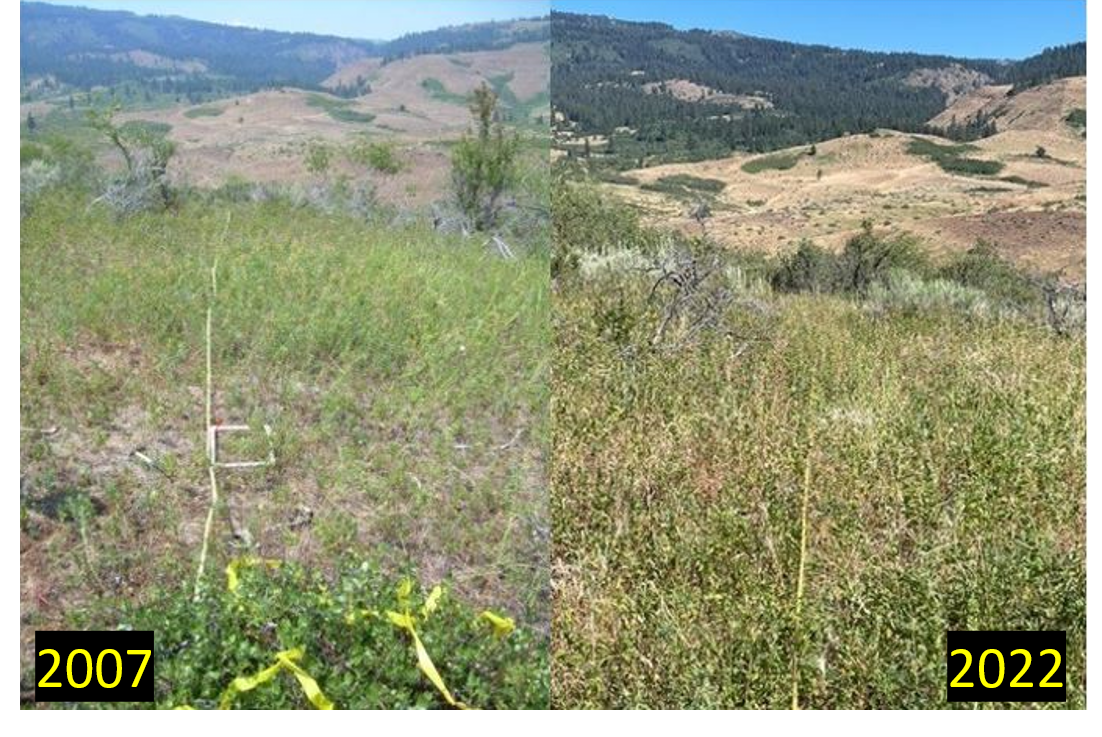

A photo point is used to visually document changes in target weed infestations and other components of the plant community over time following the release of biocontrol agents. Use permanent features in the background as reference points (such as mountains, large rocks, trees, or permanent structures) and make sure each photo includes your release point marker. Pre- and post-release photographs should be taken from roughly the same place and at the same time of year. The GPS coordinates7 are collected automatically by the app; these are important for keeping track of release locations and so that the same location can be revisited later for monitoring purposes. You can ignore the section about time spent8; this information is used only when making an observation on an established biocontrol agent population. When all of your information is entered, select Save9. This saves your report to the app’s Upload Queue. After saving a report, you will be returned to the app home screen. To submit reports, tap the Upload button (upwards facing arrow) in the top right of the home screen, beside the Settings gear icon. Please note, when EDDMapS publicly displays the data you submit, the resolution is intentionally buffered, protecting your location so that others can’t navigate exactly to that point.

There are many advantages to utilizing the iBiocontrol app and EDDMapS to record your information. Seeing all release and establishment records in your vicinity can help you and your neighbors determine if a new release is warranted and can indicate which biocontrol agents might establish more readily in your region. The EDDMapS data is also used by the curators of the World Weed Biocontrol Catalog, which keeps track (at the national and state level) of all weed biocontrol releases made worldwide.

If you are unable to use the iBiocontrol app, release information can be collected in paper format. Please refer to this release site fact sheet for forms and instructions.

Now that you’ve prepared the release site and collected the necessary information, it’s time to physically release your biocontrol agents. There are a number of factors to consider when determining the best approach, including how many, how often, when, and how.

Always remember these are live organisms, so refrain from tossing release containers around or leaving them in hot vehicles or on/near dashboards and windows on sunny days.

As a general rule of thumb, when you have just one release container, it’s better to release all the biocontrol agents together at one part of an infestation than it is to spread those individuals too thinly over multiple infestations in the region. Releasing all the biocontrol agents within a release container in one spot will help ensure that adequate numbers of males and females are present for reproduction and reduce the risks of inbreeding and other genetic problems. Guidelines for a minimum release size are uncertain for most biocontrol agents, but releases of 50–300 individuals are encouraged; releasing more than 300 individuals would be advantageous under some conditions but shouldn’t be necessary.

Often, a single release will be sufficient to establish a biocontrol agent population, especially if a large number of individuals are released. Additional releases may be necessary after a few years if your initial releases fail to establish. For species or locations where establishment is likely to be slow (e.g., sites with high levels of overwintering mortality or large, dense infestations where biocontrol agents are easily missed), planning to make releases on the same site for 2 or 3 consecutive years may increase successful establishment and reduce the time until biocontrol agent impact on target weed populations is visible. If more than one release of a biocontrol agent is available in a given year, be sure to put some distance between releases; 2/3 mile (1 km) is ideal. If possible, make more than one release per drainage or in adjoining drainages; if one of your release sites is wiped out by flooding, fire, herbicide application or other catastrophic disturbance, then biocontrol agents from adjoining release sites can repopulate it.

Establishment of biocontrol agents may be slow at sites with known high winter mortality or very large, dense infestations where biocontrol agents are easily missed. Multiple releases at such sites may increase establishment success.

Biocontrol agents are most often released during the weed’s growing season, usually in spring or summer. However, the absolute best time for releasing your desired biocontrol agent depends on the stage of development for your target weed species growing at your release site and the stage of development of your biocontrol agent population. This type of information can be found in many useful extension publications, such as the Field Guides for Biological Control of Weeds in the Northwest and Eastern North America. These and other useful publications can all be found in the Library on this website. You can also contact your local or state weed biocontrol authority for timing suggestions specific to your area.

Once at the desired release location, open the release container. When releasing adults, gently shake out all biocontrol agents and weed foliage in one small area. Do not scatter biocontrol agents throughout the infestation. Do not walk back over the area where you just made a release. Make sure the plant material in the release container does not have any weeds seeds or roots or other organisms present before dumping the contents out at the new site. Take care to dislodge any individuals hiding in or clinging to the paper towels in the release containers.

When transferring stem segments infested with biocontrol agents, take bundles of 20–50 stems and fan out one side of the bundle to provide a supportive base. Place the fanned bundles upright within dense stands of uninfested weeds. In less dense infestations or at windy locations, tying the fanned bundle against uninfested plants or a fence may aid in successful establishment. Four to five bundles should be used per site, though more or fewer may be required, depending on the infestation size. Make sure you don’t spread weed seeds or roots to new sites as this may introduce new genetic material. Also try to avoid spreading other plant or insect species to new sites as this may be accidentally creating new problems for the future.

If transferring stems infested with biocontrol agents (such as rust fungi), fan out a bundle of infested stems to provide a supportive base. In windy areas, tie the bundle against uninfested plants or a fence to ensure infested stems remain on site.

Releases of all biocontrol agents should be made under moderate weather conditions (mornings or evenings of hot summer days, mid-day for cold season releases). Making releases under these conditions reduces the immediate dispersal of stressed biocontrol agents when they’re dumped out of release containers and can significantly increase the probability of establishment. Avoid making releases on rainy days unless the biocontrol agent being released is a rust fungus (which do better under moist conditions). If you encounter an extended period of poor weather, it’s better to release the biocontrol agents than wait three or more days for conditions to improve as the biocontrol agents’ vitality will decline with extended storage. Avoid transferring biocontrol agents to areas with obvious ant mounds or ground dwelling animals that may prey upon some species of biocontrol agents. All biocontrol agents are unique and may require specific handling and release instructions, so contact your local biocontrol specialist.

Documenting outcomes of biocontrol release programs (including both successes and failures) will help generate a more complete picture of biocontrol impacts, guide future management strategies, and serve education and public relations functions. Monitoring is the most useful tool for providing this critical information in an objective way for other land managers. It helps them predict where and when biocontrol might be successful, helps them avoid releasing ineffective biocontrol agents or the same agent in an area where it is already abundant, and helps them avoid land management activities that would harm local biocontrol agent populations or worsen the weed problem.

Monitoring activities utilize standardized procedures to help determine:

Monitoring methods can be simple or complex. A single year of monitoring may demonstrate whether or not the biocontrol agents established, while multiple years of monitoring may allow you to follow the population of the biocontrol agents, changes in the target weed population and plant community, and changes in other factors such as animal populations or the climate.

If you wish to determine whether or not biocontrol agents have established after initial release, you simply need to find the biocontrol agents in one or more of their life stages, or evidence of their presence such as feeding damage characteristic of your target agent. Begin looking for biocontrol agents where they were first released, and then expand to the area around the release site. The best stages to monitor and the best timing for each depends on the biocontrol agent species and the stage of development for your target weed species growing at your release site. This type of information can be found in many useful extension publications, such the Field Guides for Biological Control of Weeds in the Northwest and Eastern North America. These and other useful publications can all be found in the Library on this website. You can also contact your local or state weed biocontrol authority for timing suggestions specific to your area.

Populations of some biocontrol agents take two or more years to reach detectable levels. So if no biocontrol agents are detected a year after release, it doesn’t mean the agents failed to establish. Revisit the site at least once annually for three years. If no evidence of biocontrol agents is found, either select another site for release or make additional releases at the monitored site. Consult with your county extension educator or local weed biocontrol expert for assistance.

If you want to determine whether biocontrol agent population densities are increasing or decreasing over time, a systematic monitoring approach is required. The Standardized Impact Monitoring Protocol (or SIMP) is the method we recommend. It’s available from a free app or through freely downloadable forms found on its own page on this website.

The ultimate goal of a weed biocontrol program is to permanently reduce the negative impacts of the target weed on ecosystem function. Success is often measured as a reduction in target weed abundance or reproductive output. To determine if biocontrol efforts are effective, there must be monitoring of plant community attributes over time, such as target weed distribution, density, or cover. Ideally, monitoring begins before biocontrol efforts are started (pre-release) and occurs at regular intervals after release. There are many ways to assess weed populations and other plant community attributes at release sites.

Qualitative monitoring uses subjective measurements to describe the target weed and the rest of the plant community at the management site. Examples include listing plant species occurring at the site, rough estimates of density, age and distribution classes, visual infestation mapping (as opposed to mapping with a GPS unit), and maintaining a series of photos from designated photo points. If repeated over time, qualitative monitoring can provide insight into the status or change of target weed populations. However, its descriptive nature generally doesn’t allow for detailed statistical analyses. We highly recommend the SIMP monitoring method mentioned above and described in greater detail in this video. This simple and relatively quick method combines elements of qualitative monitoring with the collection of quantitative data to find statistical trends over time.

Quantitative monitoring measures changes in the target weed population and associated vegetation community before and after a biocontrol agent release using statistics. It may be as simple as counting the number of target weed plants in a small sample area, or as complex as measuring target weed plant height and width, seed production, biomass, species diversity, and species cover. Pre- and post-release monitoring should follow the same protocol and be employed at the same time of year to ensure that the data is consistent and trends are easily identified. Post-release assessments should be planned annually for at least 3–5 years (and ideally longer than that) after the initial biocontrol agent release. Again, we highly recommend the SIMP monitoring method mentioned earlier for its ease of use and because it is increasingly the go-to monitoring method for land managers throughout much of North America. Watch the SIMP video.

These graphs illustrate the changes and fluctuations in leafy spurge biocontrol agent populations and the height, number of stems, and cover of leafy spurge at one site in Idaho that has been monitored since 2007.

Nontarget attack is when a biocontrol agent attacks a species that is not its target weed. To address possible nontarget attacks, you must become familiar with the plant communities present at and around your release sites and be aware of species closely and distantly related to the target weed. You may have to consult with a local botanist or herbarium records for advice on areas where nontarget plants might be growing and how you can identify them. Care should be taken in the management of your weed biocontrol program to ensure that closely related native species are identified and monitored along with the target weed.

Please be aware that there are many “look-alike” native arthropods that feed on related native plants. Correct identification by biocontrol specialists is needed to confirm such records. Please also be aware that many biocontrol agents will rest on nontarget species but not damage them. When nontarget attack does occur, a specialist can help determine the type of attack occurring:

Be aware there are several native species that closely resemble biocontrol agents, and the native species can often be found attacking numerous crop or native plant species. For example, Hyles euphorbiae (first two images) was introduced to North America as a biocontrol agent of invasive spurge species (Euphorbia spp.). The native H. gallii (last two images) is very similar in appearance and can be found feeding on fireweed, bedstraw, and several other native and introduced species.

If you observe approved biocontrol agents feeding on and/or developing on nontarget species, collect samples and take them to a biocontrol specialist in your area. Alternatively, you may send the specialist the site data and/or pictures so they can survey the site for nontarget impacts. Be sure not to ascribe any damage you observe on nontarget species to any specific biocontrol agent species because this could bias the confirmation of attack and the identification of the species causing the attack.

The vegetation sampling procedures described earlier for SIMP can be easily modified to monitor changes in density or cover of the nontarget species as well as to monitor the number of biocontrol agents observed on nontarget plants. Check with your county weed manager, extension educator, or regional weed or biocontrol specialist for more information. Collecting nontarget attack data for subsequent years can help determine if there is a population level impact or if the nontarget feeding is just temporary or only of minor consequence to the nontarget species.

Biocontrol is just one of many approaches used in the management of weeds. Several other methods and approaches are also available; in many situations, a combination of these provides the best control of target weed infestations. Integrated Pest Management (or IPM for short) is a decision-making process that combines tools and strategies to identify and manage invasive pests in a way that minimizes economic, health, and environmental risks.

Successful IPM programs incorporate various components to meet management goals, including:

IPM addresses several aspects of land management, not just how to get rid of weed populations. Land managers or landowners engaged in IPM take the time to educate themselves and others about the threat invasive species pose to the land and how management may facilitate invasion. IPM requires land managers to regularly monitor the land they manage, identifying areas where the vegetation is not meeting their management objectives and identifying reasons why. The invasion curve (at right) demonstrates that prevention is the most cost-effective solution for the management of an invasive species. When a weed becomes established, quick eradication is the next most cost-effective approach. If an invasive species is not detected and removed early and is allowed to spread, eradication becomes less likely and intense and long-term control efforts will be unavoidable. For a well-established weed population, IPM dictates that land managers map it and make plans to address it utilizing control methods most appropriate for that particular infestation and land use. After initiating control activities, IPM encourages land managers to monitor the site to determine if the control activity was successful in subsequent years. If re-treatment or additional treatments are necessary, these are applied in a timely manner with appropriate post-treatment monitoring to ensure that management objectives are being met.

Though each component of IPM is a useful tool for managing weeds, it is important to note that these components work best when used in a combined approach. Rather than applying only one tool per site (e.g., applying herbicides at one infestation, mowing at another, and using biocontrol at still another), the most effective IPM strategy is to employ as many tools as necessary at a single site in order to maximize the efficacy of each tool and ultimately reduce weed infestations to achieve land use objectives.

Education, inventorying/mapping, and prevention are important and applicable across all landscapes, whether or not weeds are already present. When target weed species are established and control methods are warranted, long-term management success is greatly improved when control methods are selected according to the size and habitat of the infestation, land use, ownership, and available resources and then integrated where appropriate. As described throughout this website, biocontrol is most appropriately used on large infestations where multiple years may be required before impacts are realized. During this time, chemical and physical control methods are best applied to smaller new or satellite populations where immediate eradication is warranted, and to the edges of large infestations to prevent further spread. For the most part, biocontrol and chemical/physical control methods should be combined indirectly. Although mowing weeds may help facilitate the spread of some mite and rust fungus biocontrol agents, in general, applying chemical and physical control directly to target weeds will likely kill biocontrol agents feeding within weed tissue. Cultural control methods work to enhance the growth of more desirable vegetation. In contrast to chemical/physical control methods, cultural control can be combined directly with biocontrol; when biocontrol agents have started to reduce a weed infestation, cultural control methods can be used to increase plant competition.

The application of biocontrol in IPM is often species-specific and site-specific, so contact your local or state weed biocontrol authority for IPM recommendations applicable to your weed of interest. For certain biocontrol agents in North America, some IPM-biocontrol integration guidelines are also available in extension publications or in outreach material available in the Library on this website.