Throughout this section, and throughout the resources on this website, we use specific terms to quickly describe a biocontrol agent’s life cycle, feeding habits, and characteristic features, all of which can help you determine the key traits that set the species apart from others. Below we give you definitions and examples of key words frequently used in basic biocontrol agent identification. All technical terms used throughout this website are also defined on the glossary page, or you can hover your cursor over select words to see definitions immediately.

Classical biocontrol agents may be found in a number of taxonomic groups. The majority of approved biocontrol agents are animals in the phylum Arthropoda. More specifically, most biocontrol agents are insects (class Insecta) in the orders Coleoptera (beetles), Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), and Diptera (true flies). In addition to insects, there are also mite, nematode, fungi, bacteria, and virus biocontrol agents. An understanding of basic biocontrol agent biology and anatomy will help for the recognition and identification of species used as biocontrol agents of weeds.

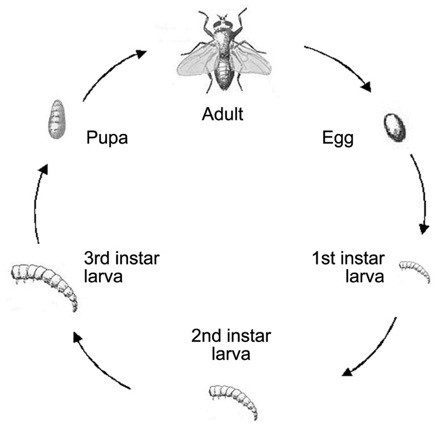

Insects are the largest, most diverse class of animals in the phylum Arthropoda. Most insects used in biocontrol have complete metamorphosis, which means they exhibit a life cycle with four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult (diagram at left, below). Insects in the orders Hemiptera (true bugs) and Thysanoptera (thrips) have incomplete metamorphosis, which does not include a pupal stage. Instead, their young are called nymphs and resemble the adults to a large degree (diagram at right, below). The transformation from nymph to adult primarily involves the development of wings (only in some species) and functioning reproductive organs.

All adult insects have an exoskeleton (a hard external skeleton), a segmented body divided into three regions (head, thorax, and abdomen), three pairs of segmented legs, and may have one or two pairs of wings. The head of an adult insect has one pair each of compound eyes and antennae. Immature insects must molt their exoskeletons before growing to the next stage, and larval stages between molts are called instars. During the pupal stage, insects change from larvae to adults. Insects do not feed or molt during the pupal stage. Adult insects emerge from the pupal stage and do not grow or molt.

Beetle larvae are either grub-like without legs, or they have only three pairs of legs, all located close to the head. Many are pale white with a brown or black head capsule, and all have chewing mouthparts. Beetle pupae have well-developed appendages that are not fused to the body. Adult beetles also have chewing mouthparts. Adults are hard-bodied with tough exoskeletons and possess two pairs of wings. The two front wings (elytra) are thickened and meet in a straight line down the abdomen, forming a hard, shell-like, protective covering. The two hind wings are membranous, larger, and used for flight; these are folded under the elytra when not in use.

Examples of the life stages of beetle biocontrol agents: the knapweed root weevil (Cyphocleonus achates) and St. Johnswort beetle, Chyrsolina quadrigemina.

Moth and butterfly larvae (known as caterpillars) have a toughened head capsule, chewing mouthparts, and a soft body; they are active feeders. Moth and butterfly larvae have three pairs of true legs located close to the head, plus additional leg-like structures (prolegs) farther down the abdomen. Prolegs act as anchors that hold the larva tightly in place during movement of other body segments. The pupal stage of moths and butterflies can be naked or enclosed in a cocoon, depending on the species. Adult moths and butterflies have two pairs of membranous wings covered with powder-like scales, prominent antennae, and coiled mouthparts adapted to siphoning nectar from plant flowers. Adult moths and butterflies used in weed biocontrol usually feed very little, if at all.

Examples of the life stages of moth biocontrol agents: the larva, adult, and cocoon of the toadflax defoliating moth (Calophasia lunula); and the naked pupa of the leafy spurge hawk moth (Hyles euphorbiae).

Many insects have the word “fly” in their name, though they may not be true flies. In the common names of true flies, “fly” is written as a separate word (e.g., house fly) to distinguish them from other orders of insects that use “fly” in their name (e.g., dragonfly in the order Odonata). Larvae of most true flies, called maggots, are leg-less and worm-like. The pupa of many true fly species is contained inside a puparium (the hardened last larval skin which encloses the pupa). Adult true flies are readily distinguished from other orders of insects by their single pair of membranous wings and typically soft bodies.

Examples of the life stages of true flies: the yellow starthistle peacock fly (Chaetorellia australis) and bull thistle seedhead gall fly (Urophora stylata).

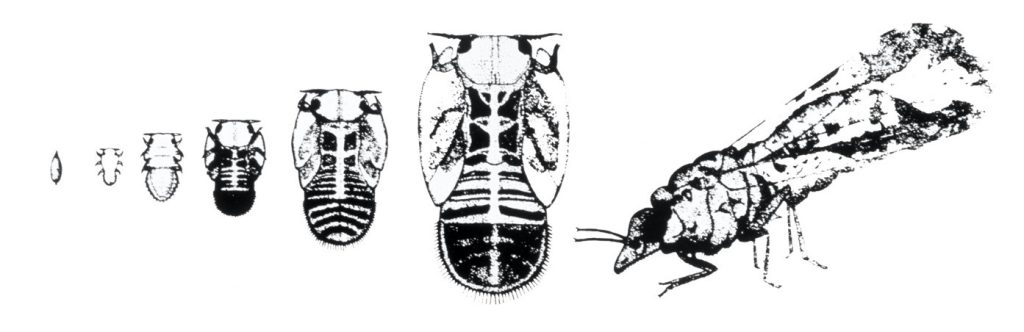

Species in the order Hemiptera do not have a pupal stage separating larvae and adults as many other insects do. Instead, their young are called nymphs, and they resemble adults more and more during each instar. Many adult Hemiptera possess two pairs of wings, though some are wing-less. In winged individuals, the hind pair is membranous, and the two front wings may be entirely membranous or only membranous at their tips and hardened at their base. A defining feature of Hemiptera is their “beak” which allows nymphs and adults of plant-eating species to feed by piercing plants and sucking out the cell contents.

Examples of the life stages of a Hemiptera biocontrol agent: Aphalara itadori, the knotweed psyllid.

Thrips do not have a pupal stage separating larvae and adults as many other insects do. Instead, their young are called nymphs, and they resemble adults more and more during each instar. Adult thrips can be wing-less or have two pairs of stalk-like wings with long hair fringing the margins. There are two actively feeding nymphal stages for all thrips and 2–3 inactive (non-feeding) stages. Adult and actively feeding nymphal stages of plant-eating species feed by piercing plants and sucking out the cell contents.

Examples of the life stages of Frankliniella occidentalis, the western flower thrips.

Like insects, mites are in the phylum Arthropoda and have an exoskeleton; however, they belong to the class Arachnida, whose adult members are usually characterized by having eight legs (compared to the six legs of insects). In some mite species, the first immature stage is called larva; mites in this stage have only six legs. The second immature stage is called a nymph and has eight legs. Nymphs typically resemble adults. Some mite species do not have a larval stage, and some mite families have only four legs. Larvae, nymphs, and adults all feed by piercing and sucking cell contents.

Examples of the life stage sof mite biocontrol agents: gorse spider mite (Tetranychus lintearius) and bindweed gall mite (Aceria malherbae).

Nematodes, or roundworms, are animals in the phylum Nematoda. They are cylindrical, unsegmented worms that are typically 0.1–2.5 mm long and 5–100 µm thick. They have tubular digestive systems with openings at both ends. Eggs hatch into larvae (juveniles) that resemble adults but have underdeveloped reproductive systems. Nematodes parasitic on plants have four juvenile stages. There are often two or three generations a year, and juveniles typically overwinter in plant material.

Fungi belong to their own kingdom: Fungi. Most fungi used in North American biocontrol are rusts, which are in the phylum Basidiomycota. Rust fungi are obligate parasites, meaning they require a living host to complete their life cycle. Rusts typically attack leaves and stems of the host plant. Rust infections usually appear as numerous rusty, orange, yellow, or even white-colored spots (pustules) that rupture the leaf surface and release spores that resemble colored powder (typically yellow, orange, or brown). Most rust infections are local spots, but some may spread internally through the plant. Rusts spread from plant to plant mostly by windblown spores, although insects, rain, and animals may aide in the rust transmission and infection process.

The life cycle of rust fungi can be very complicated (see diagram). Rust fungi are termed macrocyclic when they produce five types of spores. Teliospores usually overwinter in dormancy, these germinate to produce basidispores that infect target plants in spring. Pycnia are then produced which yield pycniospores (aka spermagonia) that are self-incompatible and are cross-fertilized with receptive hyphae on other plants/genets/etc. to eventually yield aeciospores. Symptoms at this stage include yellowish chlorotic lesions, often with raised centers, which turn into orangish-brown or rusty-brown pustules that produce large amounts of urediniospores. In most rust fungi, it is often the urediniospores that are wind-borne and go around infecting plants throughout the growing season through several “generations”. (However, for some rust species, such as the Canada thistle rust Puccinia punctiformis, it is the aeciospores that are wind-borne and cause local infections.) In autumn at many locations in North America, lesions form at the bases of infected plant shoots. These produce teliospores that overwinter in dormancy.